Introduction

Islamic Influences on Moroccan Culture: Morocco is a diverse country in Northwest Africa with a rich cultural heritage derived from its unique history and geographic position. As a predominantly Muslim country, Morocco’s culture has been deeply influenced by Islamic traditions for centuries. However, Moroccan culture also incorporates indigenous Berber cultural roots and influences from Europe, sub-Saharan Africa, and the wider Arab world. In this article, I will explore some key ways Islamic beliefs and practices have impacted and shaped Moroccan culture.

The Arrival of Islam in Morocco

Islam first arrived in Morocco in the early 7th century AD through Arab traders and later military conquests. However, it was not until the 12th century that the Almohad Islamic movement firmly established Islam as the dominant religion in modern-day Morocco through conquest and religious reforms. Before the 12th century, vast areas of Morocco were largely Berber, with some Christian and Jewish communities.

The arrival and establishment of Islam brought significant societal and cultural changes across Morocco. While the indigenous Berber languages and cultural traditions endured, Berbers gradually began to speak Arabic and adopt Islamic beliefs, practices, and forms of social organization. New mosques, madrasas (schools), and Islamic architectural styles began to appear. Islamic dietary restrictions, clothing norms, marriage customs, and festivals became ingrained aspects of Moroccan culture and society.

Over subsequent centuries, Morocco developed its unique brand of Islam that blended with and was influenced by local Berber customs. To this day, Morocco remains a culturally conservative Muslim country, with over 99% of the population identifying as Sunni Muslims following the Maliki school of Islamic jurisprudence. Islam shapes daily routines, social values, arts, regional traditions, and a strong sense of Moroccan national identity.

The Role of Sufism

Sufism, or Islamic mysticism, was essential in spreading Islamic influences and integrating local Berber traditions into Moroccan culture. From the 12th century onward, Sufi brotherhoods (tariqas) became influential across Morocco society. The main Sufi orders that established widespread followings include the Tijaniyyah, ‘Alawiyyah, and Boutchichiyya orders.

Sufi shaykhs and saints helped populate areas, establish new settlements, and spread Islam at the grassroots level across Morocco. Their zawiyas (meeting places) served religious functions and became centers of learning, hospitality, and cultural exchange. Annual mousse festivals developed at the shrines of prominent Sufi saints, featuring performances of devotional music, dance, poetry recitals, and ritual trance practices. Many of these moussem traditions blend Islamic spirituality with local cultural styles and folklore.

Additionally, the focus of Sufism on inner purification, mystical experiences of divine love, and spirit possession ceremonies integrated well with existing Berber religious beliefs. This facilitated the conversion process for rural Berber communities. In many regions, indigenous seasonal agricultural festivals and trance rituals took on an Islamic veneer while maintaining pre-Islamic functions and symbolism. For example, the Aissawa brotherhood in the Draa Valley region incorporates spiritual dances, music, and possession practices with Sufi Islamic meanings.

To this day, Moroccan folk and popular religious practices retain strong Sufi influences. Zawiyas continue serving local communities, annual mousses remain vibrant cultural events, and trance rituals assimilated Sufi expressions. The legacy of Moroccan Sufism illustrates how Islamic beliefs and practices both impacted and blended with indigenous artistic traditions.

Social Structures and the Family

Islam significantly affected Moroccan social structures, morality, and the central importance of family life. Morocco developed as a patriarchal, family-centered society reflecting Islamic family law concepts. Marriage is considered a religious obligation in Moroccan culture. Extended family units, with strong bonds of mutual assistance, are the primary social safety net.

Islamic concepts of modesty, virtue, and proper gender roles are deeply ingrained. For example, premarital relationships are typically forbidden, and divorce remains somewhat stigmatized. However, as in other Muslim societies, Morocco has become more socially liberal in recent decades – especially in urban centers – while still upholding conservative Islamic traditions.

Culturally, hospitality, respect for elders, and strong family lineage (ssila) are essential. These values have pre-Islamic Berber roots but were emphasized and formalized through Islamic teachings. Maintaining family honor and a good reputation within the community (izz) is a powerful social motivator.

Naming conventions also demonstrate Islamic influences on Moroccan identity and family structures. Virtually all Moroccans now have three personal names – the first is an Islamic name, the second is a familial surname, and the third is the father’s given name. This replaced older Berber naming practices but still acknowledges tribal roots through the patrilineal name.

Diet and Cuisine

Moroccan cuisine provides a rich example of cultural blending following Islamic guidelines but retaining indigenous Berber flavors and culinary traditions. While Moroccans follow Islamic halal dietary restrictions on consuming pork and alcohol made from grapes or dates, Moroccan cuisine shows no shortage of diversity or flavor.

Many staple Moroccan dishes developed as ways to observe fasting during Ramadan using indigenous spices and ingredients. Classic tagines, harira soup, and semen flatbreads reflect this heritage. Tagine stewing in clay pots likely originates from medieval Al-Andalus to flavor home-cooked meals while fasting.

Berber culinary traditions were adapted to be halal and are now fully integrated with an Islamic identity. For example, the Berber staple dish of couscous gained religious meanings during Friday communal meals. Ancient foraged and wild foods like wild olives, snails, and edible flowers are still enjoyed without contradicting Islamic guidelines.

Exotic Moroccan salads incorporating fresh produce, nuts, dried fruits, and herb preserves reflect economic and culinary exchange through Moroccan history. Arab, Persian, and Ottoman preparations have left imprints alongside indigenous foods. However, Moroccan cuisine retains its authentic fusion of Berber heartiness with Arab-Andalusian refinement and spice. This fusion symbolizes the dynamic cultural blend of Moroccan society over 15 centuries of Islamic influence.

Language

Arabic has profoundly impacted Moroccan culture as the language of the Quran, religious teachings, business, and formal domains. However, Moroccan Arabic (Darija) developed independently from Modern Standard Arabic with heavy Berber, French, and Spanish influences. This dialect, spoken by all Moroccans, became the primary mother tongue while still relying on Arabic script.

Darija maintains significant Berber vocabularies – especially for indigenous flora and fauna. Besides Berber loanwords, Darija uses French and Spanish terms (like ‘souq’ marketplace instead of Arabic ‘suq’). The language exhibits a playful, localized character compared to formal Arabic. However, its widespread use has been crucial to disseminating Islamic concepts across Morocco’s diverse populations for over a millennium.

Classical and Standard Arabic knowledge remains essential for reading the Quran and Islamic literature. However, the development of Moroccan Arabic as the lingua franca symbolizes the dynamic interplay between Islamic and local Berber cultural influences. Language became a bridge rather than a barrier, facilitating Islamization while preserving diversity.

Islamic Influences on Moroccan Culture: Arts and Architecture

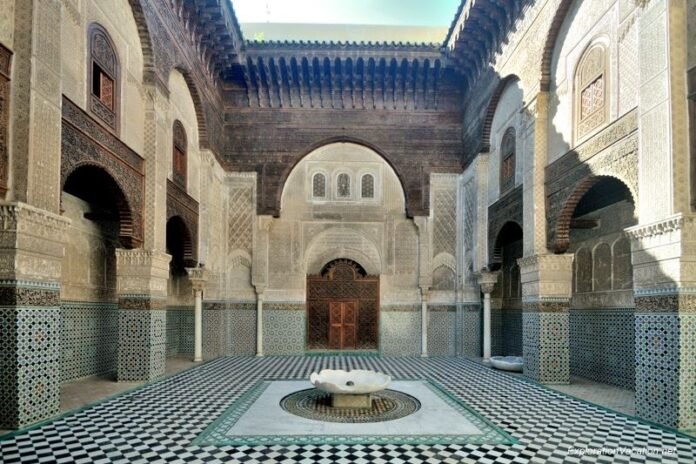

The profound cultural influences of Islam are evident in Moroccan art forms, architecture, decorative arts, music, and calligraphy. Moroccan architects pioneered the fusion of Islamic architecture and indigenous traditions, producing a distinct Moroccan style. Elements like elaborate stone carving, terra cotta tilework, intricate stucco plasterwork, arched entries, and courtyard gardens all fuse influences from Al-Andalus, Middle East, and Berber building traditions.

Moroccan mosques exhibit elaborate mihrab prayer niches, minarets, and domed roofs reflecting the aesthetics of the Umayyad caliphate in Andalusia. Yet indigenous features like carved cedarwood ceilings and wind towers were adapted to the Islamic architectural repertoire. Moroccan madrasas similarly use innovations of hypostyle layouts, ablution fountains, and ornate decorative programs to embody the Islamization of learning spaces.

Palaces, riads, and homes exhibit the marriage of Andalusian stucco architecture to Berber structural techniques of voussoirs and carved cedar. The highly symbolic geometric and floral stucco decor arose in Islamic societies but found lush expression in Morocco. Using Berber craft traditions, materials like ceramic zellij tilework imbue spaces with Quranic blessings.

Moroccan arts illustrate this balance as well. Calligraphy employs the complex Kufic and Thuluth scripts to adorn mosques yet retains Berber cursive scripts for everyday uses. Miniature painting and bookbinding arts showcase Moroccan court cultures, fusing Persian techniques with indigenous themes. Moroccan jewelry, pottery, and metalwork were developed in the context of Sufi talismans and amulets using pre-Islamic Berber symbols recontextualized through Islam.